You ask about my childhood.

Children always ask about the childhood of the adults taking care of them, as if they cannot believe that we once were children, too.

Let me assure you, we were.

I was.

I once was a child, of your very age.

How did you become a harper, you ask.

I raise my eyebrows at you.

You have been taught not to ask questions of a personal nature.

But you are stubborn, and inquisitive.

Just as I once was.

So you ask again.

If you promise to go to sleep right after the story, I will tell you.

Very well, I will tell you.

***

I grew up in a village in Adornond, the Westfold of Rohan.

A small village, way up in the Ered Nimrais. The men of my village are hunters and fierce warriors.

But we also breed the famous mountain goats of the Ered Nimrais. You have probably heard of them, even if you cannot place the name of our village. From the wool of the Nimrais goats the finest and lightest fabrics in all of Arda are spun. Fabrics, which are light as gossamer, but nevertheless warmer than the thickest fur of bear or wolf.

Our fabrics are priceless.

Only kings and queens, the highest lords and ladies can afford to buy them, because the wool has to be picked from the thorny thickets of the highest plateaus of the Ered Nimrais in spring time each year. The Nimrais goats cannot be shorn. Each year we gather the wool of the goats of the Ered Nimrais, and we spin it into silky threads. From those threads we weave the most precious fabric in all of Arda. But there never is much of it. Most years only one single piece of clothing can be made from it. One kingly cloak, one queenly dress. Each gown is worth the ransom of a kingdom.

But it is a harsh life, up here in the mountains. No matter what the traders pay for the Nimrais cloth, life stays harsh up here in the mountains. It is a lonely life, up here in the mountains. Traders or travellers only seldom make their way up the narrow, winding paths to our village.

If the snows are heavy during the winter, the village cannot be reached for months. Sometimes we cannot leave the houses for weeks at a time.

News of the world mean little to us, up here in the mountains. The coming and the going of evil, the growing and the waning of centuries, the songs and stories of Aman or Arda rarely touch our lives, up here in the mountains.

But there was one winter that was different.

There was one winter, when a visitor came to our village.

Sometimes even up here in the mountains strange things happen.

I will tell you of that winter and that visitor.

It was in the winter of the year 3020, the winter after the evil enemy in the east was vanquished. We knew about that, because even from our small village a group of men had ridden to that war, and only three had returned.

It was a cold winter, with high snows and many storms. The paths down to the valley had been snowed shut the first time early in October. The visitor came at the end of October, on one of perhaps three days, during which the passes leading up to our village could be conquered before winter came to stay.

He was a wandering bard, a travelling harper, a singing story teller. There are many story tellers and travelling musicians who roam the lonely roads of Arda. Most are nothing but vagabonds, hardly able to keep the simplest rhythm or sing a children’s tune, with no memory for verse of rhyme at all. But even one of those would have been welcomed in our village.

The winters are too long and too lonely, up here in the mountains.

But this one, this one was not a vagabond.

We did not know who he was.

He never gave a name.

He was blind, and clothed in rags, a tattered black coat billowed around his frail frame of a body. He had a gnarled staff, which he used to find his way and to lean on wearily. On his back was a small pack and an ancient harp.

He looked like an old man. Deep lines of age furrowed his face. He walked with bent shoulders, as if the weight of the world rested heavily on his back. His hair seemed to be grey. A dirty, dark grey colour, faded and worn. His hair was unkempt, a great, grey straggling mane, flowing down over his shoulders.

He was blind. His sight must have been taken with burning branches thrust into his eye-sockets until nothing was left there, but black ruin and deep lines of pain that furrowed his face.

His left hand had been ruined, too. His hand must have been taken by the torturer and must have been thrust into the coals of the very fire that had held the branches, which had taken the light from his eyes. His hand must have been held in that fire until nothing was left of his palm but black ruin and deep lines of agony that furrowed his face.

How he ever made it up the mountain all alone, blind and burdened as he was, I will never know. But he was there, one morning at the end of October. He knocked on the door of the chief of our village. He put forth the request that is traditional among the travelling singers and story tellers, and was granted it. In exchange for a bed and a meal a day, he would keep us entertained during the long, lonely winter.

There was no way to refuse this plea.

Yet our chief was wary. Times had been dark, and there was something about this old man that was different. Something was about this man that was strange and uncanny. But in the end, our chief invited the bard in and offered a bed in his own house as it is custom and honour demands it.

I was only a child then, and more oblivious than others of this blind bard’s strangeness.

I went to him that very first evening, as I went to my animals, my friends, my aunts and uncles, and even to my forbidding father, because my mother had died giving birth to me and I grew up wild and uncouth, knowing nothing of manners and men.

The bard sat in the corner of the great raftered hall in the house of our chieftain, where all people gather to spend the long evenings of winter, in shared labour and laughter, spinning and singing, as the hours slowly snow by.

He sat in that corner very silent, very still. I could see the dirty linen covering his eyes and I had been told that he did not see. The greatest bards, it is said, cannot see. So I knew that he could not see, and yet, as I approached him, I was aware that he knew exactly where I was in the room before him.

He sat still. He sat in silence. As if he did not want to frighten me away. So I approached him, warily, but filled with curiosity. I hesitated a few feet away from him. I stared at him in childish fascination.

“A child.” He said. “Look all you want, little one. An old man as unkempt as I am you will never see again.”

“Why are you so ugly?” I asked. As I said, I grew up wild and without any ways of politeness, chasing goats and gathering wool. Of the world and its manners down below I knew nothing.

“Perhaps because I am ugly,” he answered. And I understood that he did not mean his looks, but what he was. Whatever that was.

I cocked my head to the side and considered his answer. His voice was clear and deep. His voice was young and pure. His voice was not ugly at all.

“I don’t think so,” I said finally. I did not think that someone with an innocent voice could be ugly, no matter what he looked like. I was also simply intrigued by this strange old man.

“Tell me, child, I know we are in a great hall, but what does it look like? Will you describe it for me?” The old man asked.

“Certainly,” I said. I walked up to him and clambered on his knees. I was about five years then. I had decided to trust him. So I went to his knees as a kitten does, driven by instinct, not inhibited by etiquette.

He was astonished, I think. But only for a moment. Then his arm went around me and he asked again. “Tell me, child, what does this hall look like?”

I looked at the hall. I had known the hall all my life. I had never thought about what the hall looked like. In a way it was as if I saw the hall for the first time that evening, as I looked at it for the blind bard, sitting on his knees.

“It is a great hall,” I said. “It is THE great hall,” I repeated emphatically. “Everyone comes here. It has great rafters in the ceiling. Huge beams of wood. Like, of huge trees. Such as grows down below, but not up here. They brought them up from down below. Long ago. And the hall’s all decked out for the winter festival.”

Then I added importantly, “They do it with the first snow. I do know that down below they do that only much later, but here we do it differently. ‘Cause we are up in the mountains.”

“How is the hall decked out?” The old man asked.

“It’s mistletoe and holly, they hang it from the rafters.” I answered.

“That’s what they did in the old world, too,” he said. “That’s what they did in Hollin, the land that was once called Eregion, thousands of years ago. Mistletoe and holly, to ward off the darkness.”

“Did they?” I had no notion of time beyond the passage of the week and the coming of spring. Of Hollin or Eregion, or indeed of Gondor, or even my own country, Rohan, I knew nothing. My world was “up here in the mountains”, and “down below”.

“But the darkness has passed,” I told him. That was a bit of adult wisdom even I had picked up during the last year. Darkness and war and the enemy had been talked about even way up here in the mountains. Victory and the new king and his elvish queen and the new alliance between Rohan and Gondor had been talked about even up here, although of that I only remembered the name of the queen, and nothing else. But the name had been so strange and so beautiful that I had remembered it.

“Arwen,” I said. “The darkness is gone and there’s a new queen.”

The blind bard started at that, but he did not say anything.

Then we were interrupted.

“A song, a song,” the raucous voices of the gathered men called out above the noise of many tongues chatting to the clicking of needles and the whirling of the spinning wheel. “A song, a song,” was the demand that rose above the general confusion of talk and laughter and many voices, of men and women, oldsters and children, gathered to spend the cold, dark evening of winter in the shared warmth of company and conversation.

The old man slid me down from his lap, and took his harp in his hand.

With a few hesitating, uncertain steps he reached the open space in front of the big fire place.

In a gesture that seemed to me both grand and glorious, the bard threw the tattered remains of his robes back over his shoulder. High he held his head, turning unseeing eyes to high rafters hung with holly and mistletoe, warding off the darkness. Every face was turned to him as he stood there, and I realized that despite his age, he was still tall, and there was a strange grace to his figure that seemed to belong to another world.

The world down below?

Firmly he took his harp in his ruined hand.

Firmly he struck the strings.

Furrows of pain and agony in his face creased together as his mouth moved to sing.

I remember every song the blind bard sang that winter, and there were many.

This first song was a simple song. A song that went to the hearts of the villagers and put them at ease.

“The road goes ever on and on…”

The women liked the song and they smiled at the old man, and my sister whispered to me that the blind bard was the best singer under the sun.

***

I liked his songs well enough. But I liked him better. He was the first from down below I ever met, and I was intrigued. The others, especially the warriors and hunters of the village, did not like him. For some reason they looked down upon him because of his disability, because of his blindness. He was not only old, he was a cripple. In their eyes, he was not a man anymore.

The women were a little frightened of him, and kept the other children away from the harper. I was but a waif, and no one cared what I did, to whom I talked, and so I spent the long days of this winter in the company of that blind bard.

I don’t think he liked me.

There was a deep bitterness about him and an even deeper loneliness that did not care for company. He said he was cursed. I said that I did not care.

He did not send me away.

Weeks passed in the company of songs and stories such as we had never heard before.

Of elves he sang, and of heroes, of dragons and halflings and smouldering mountains and he struck his harp into lilting tunes of dancing and lullabies, as was his duty, to entertain and to please the gruff voiced warriors of a lonely village and the rough mannered hunters of the mountains high, their simple, unpolished women and their timid, gaping children.

***

Then mid-winter came and he sang of Gil-galad.

The great fire of mid-winter eve roared in the fire place. Garlands of ivy and holly and mistletoe were strung up in the hall, the silver penny had been dropped into the grits, the roast was being turned slowly by the patient efforts of the spit-dogs, going round and round and round, ring a ring a rosy, until the roast was done.

Much as the hall we were decked out, in what finery we had, rough homespun fabrics in drab colours of grey and brown and green. Not for us the Nimrais goats lost their fine silken hairs in spring, but for the kings and queens down below, in that other world of roads and plains and cities.

Beer and mead and liquor, mulled wine and cider had been poured and rough rose the voices of the warriors, demanding entertainment, demanding honour and homage.

So swiftly to his feet rose the blind bard and took up his harp the harper.

And it was mid-winter, and he sang of Gil-galad,

“Gil-galad was an Elven-king.

Of him the harpers sadly sing…”

In high harmony the harp sounded, stilling the villagers’ clamour and drunken tongues’ debates. Merriness and laughter the bard moulded into awe of battles lost and won, in ages long gone and almost forgotten. Palaces he built in harmony and rhythm and deadly foes he destroyed in ringing dominants.

When he ended, silence rang through rafters and hard holly.

Then, one and all, the men rose from their seats and raised their cups to his glory.

“Hail!” They called, and, “Hail!”

They could not but cheer such valour, even long vanished.

They could not but praise such bravery, even forever broken.

They could not but honour such heroic hands, even if it was a harp they held, and not a sword.

“Hail,” they shouted with sharp voices, and offered the blind bard a cup to join their drunk delight of battles long ago. They said he was the greatest singer the world had ever known, and they hailed him with high honour.

He accepted the cup, which they had poured for him, but he did not smile in answer to their cheers.

***

“What do you see?” I asked him several days later.

The winter had moved on, but still the snow was piled too high to leave the village, and there was no passage to be had to the world down below.

I was a child then, I did not understand darkness and blindness.

“Pain I see,” the blind bard said. “Death I see. And anger. Blinded pride I see. Stubborn, blinded pride that still lives on. And I can tell you even more.”

“What can you tell me?” I asked. I was not afraid of him. I was only curious.

“I can tell you what you see.” He replied.

“Well, I could tell you that,” I retorted. “I am not blind. I know what I see.”

He laughed at that, softly. “And perhaps you do, child. Perhaps you do! After all, it is said that in the eyes and the mouth of the child lies the truth. Tell me what you see, then.”

“I see an old man,” I said. “An old man, who has been hurt by bad people. Did you fight in the war? Your hand is hurt and your eyes are, too. Because you are blind, you are the greatest bard of all. But you don’t like the songs you sing.”

“Old I am and blind I am, so much is obvious. But you are right. I don’t like the songs I sing.” He replied in his gruffest voice.

“Why? They are very beautiful,” I said. “I like them. And how old are you anyway?”

“Let me tell you what I think that you see,” he said, ignoring my comment. “I think you see a fool before you. A stubborn, blinded fool, whose pride and pain is paid for in the coin of a cold curse clinging to his soul through centuries uncounted. Singing sad songs of glory is my fate, because I failed when humility and silence was called for. I shape into harmony how pride wins through honour and how fools decide the fates. You are right. I do not like my songs. Where are the heroes? Where are the songs? What good will they do, when the day is done? I could wish that Valinor, should I reach it evermore, be songless, so I might forget useless foray and fruitless victory.”

“You are in a very bad mood,” I said to him, because I did not understand what he had been talking about. “And the darkness is gone. And you did not tell me how old you are.”

“Yes, I am in a very bad mood, little one. I am a very bitter blind bard, in a very bad mood. And the darkness is not gone. It lives in us, in every one of us, and out there, too. It will be back.” He told me. “And you don’t ask how old someone is. It isn’t polite.”

I think he maybe wanted to scare me off. But I did not go away. I was stubborn just as stubborn as he was.

“I like your songs and the way you play them on your harp. I like singing and playing. Would you show me how?” I asked, undaunted.

“Didn’t I just tell you that I don’t like my songs?” The bard asked in return. I shrugged and stared at him. I wanted to learn how to sing. And I did like his songs, even though they were so sad.

He sighed. “Children never give up. Very well. This is how you hold the harp…”

That night he sang of Frodo of the Nine Fingers and the Ring of Doom, and the cheering would not stop for a long, long time after he had finished.

The next night he thrust the harp into my small hands.

“Now you sing,” he said.

They laughed, of course. But they did listen. And they did applaud.

***

Finally the snow melted, and the bard took his leave of our village, high up in the mountains.

He took his songs with him and his harp, and a beautiful cloak fit for a king that the chieftain had given him in honour for sad songs sung for heroes fallen in the war against the darkness.

He looked like an old man, and he was blind. Apart from his new cloak he was clothed in rags. He used his gnarled staff to find his way and to lean on wearily. On his back was his small pack and his harp. Deep lines of age furrowed his face, and he walked with bent shoulders, as if the weight of the world rested heavily on his back. His hair grey faded hair flowed in a straggling mane down to his shoulders.

His eye sockets were nothing but black ruin, covered by dirty linen bandages, and deep lines of pain furrowed his face. His left hand was nothing but black ruin, furrowing his face with deep lines of agony.

He moved slowly, hesitatingly. He could not see where he was going, but he went there anyway. And this time, he did not go alone. Slow blind step by slow blind step he led me down from the mountain to the world below.

I do not know who he was.

He never gave his name.

But he took me with him, down from the mountain to the world below.

***

That is how I became a harper.

***

Now you stare at me with wide eyes and your mouth open.

But who was he, you say.

Who was he?

Who was he, to take me from my home?

Who was he, to teach me to play ancient songs on an ancient harp?

I shrug.

I still do not know why he allowed me to come with him.

I still do not know why he gave me his harp.

I still do not know his name.

Perhaps he had done something like that before.

Perhaps he will even do it again.

But hush now, little Prince of Rohan, and sleep, as my harp plays.

No high song of sorrow you will hear from me,

but low, soft songs and humble lays.

One more question?

But only one!

What happened to the blind bard?

I do not know what happened to him.

One day he went away and never returned.

Perhaps he is still out there somewhere, walking in his hesitating, blind steps along a long, lonely road.

Perhaps he still sings somewhere, songs of high sorrow, his blind eyes full of ancient stubborn pride.

Perhaps he is still there.

Perhaps he will always be there.

You think you have guessed his name?

Really?

***

Alright, one more lullaby.

But only one.

And then you go right to sleep.

Promise?

Here we go.

***

Yes, little Prince of Rohan, if you asked me to guess this blind bard’s name, I would also say it was Maglor who came to our village that winter’s day and taught me how to sing and play.

But you did not ask, and therefore I will not guess, but only play one last lullaby for you on this ancient harp.

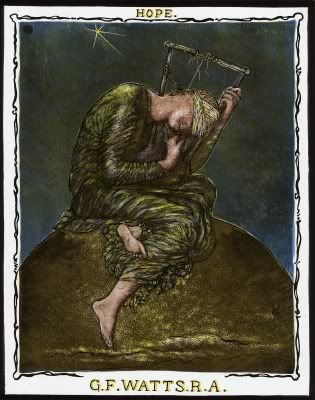

The Bards (by Sidney Keyes, 1922-1943)

Now it is time to remember the winter festivals

Of the old world, and see their raftered halls

Hung with hard holly; tongues’ confusion; slow

Beat of the heated blood in those great palaces

Decked with the pale and sickled mistletoe;

And voices dying when the blind bard rises

Robed in his servitude, and the high harp

Of sorrow sounding, stills those upturned faces.

O it is such long learning, loneliness

And dark despite to master

The bard’s blind craft; in bitterness

Of heart to strike the strings and muster

The shards of pain to harmony, not sharp

With anger to insult the merry guest.

O it its glory for the old man singing

Dead valour and his own days coldly cursed.

How ten men fell by one heroic sword

And of fierce foray by the unwatched ford,

Sing, blinded face; quick hands in darkness groping

Pluck the sad harp; sad heart forever hoping

Valahalla may be songless, enter

The moment of your glory, out of clamour

Moulding your vision to such harmony

That drunken heroes cannot choose but honour

Your stubborn blinded pride, your inward winter.